PRESUMPTION OF PATERNITY, BUT NOT EQUALITY (The Massachusetts Review)

IN LATE JUNE, a friend shot me a text: “Let me know if you want to march with [me] on Pride here in NYC.” I grappled with the question, the shame it brought to the fore. In my inbox was an email from my attorney sent just days before: “Nicole—attached is the notice of the argument en banc. It is scheduled for Harrisburg on August 9th.” At the time of year when I and other queer folks parade pride in ourselves, communities, and families, I was involved in another kind of spectacle. One in which the Pennsylvania Superior Court would determine whether the child my wife and I brought into this world is mine.

I SPENT A DECADE prosecuting intimate partner violence and po- lice. While in law school, I learned that, in our courts, presumptions are tools judges use consistently to decide tough legal questions. There are legal presumptions we widely accept: a criminal defendant is presumed innocent until proven guilty; a missing person who has not been heard from for seven years is presumed dead; a child born of a married couple is presumed to be the husband’s, regardless of biological relation. In the context of family law, this is the most significant legal presumption there is.

This presumption, though, only applies to cis-men. It does not apply to cis-women wives who, though not biologically or gestationally related to a child, have taken on the full breadth of financial responsibilities, emotional devotion, and medical actions necessary to bring that child into the world. I learned this unfair truth not as a lawyer or law student but as a litigant.

THE IMPORTANCE OF DIALOGUE ACROSS DIVIDES (Oprah Daily)

The lighter clicks as his mother fans it beneath a heroin-filled spoon. His 5-year-old belly growls. A foster mother’s fist thunks against the sink as she thrusts his hand into the garbage disposal’s spinning teeth. An officer’s fist crunches into his nose at a residential community for at-risk boys. Clankgo the handcuffs around 11-year-old wrists—the work of a truancy officer who correctly identified him as a runaway, but never asked why.

This is the soundtrack to a splintered life.

In That Bird Has My Wings, Jarvis Jay Masters’s debut memoir, readers are thrust into painful scenes familiar to too many Black American boys born into addiction and poverty. His story reads as a blueprint for the incarceration pipeline: The small child siphoned off from the most basic forms of care becomes the young man who seeks safety and shelter through the promise of crime—and is punished accordingly. This is where the story, as it has for many, could have easily ended.

Instead, Masters transforms himself again.

REMIX THE PLAN, RETURN TO THE PURPOSE (Teachers & Writers Magazine)

The waiting room was cramped. Self-care bulletins, hotline advertisements and glossy Department of Probation postings were taped on its green walls. In slanted cursive, a child-size Post It cautioned, “Please note, NYC Dept of Probation POs work 7 days per week. Any Departmental representative may/can visit your home, employment, program, school, or family members home. Thanks.”

Wide-legged and cross-armed, a young man slumped into a seat beneath the warning. Across the room, under a baseball cap’s brim, another’s eyes were closed, his head hung low as he napped. Next to him, a woman no older than twenty-five cupped her cheek with a palm, sculpted nails pressing into hair slicked into a high bun. Well past her fifties, a grey-headed woman sat behind a personal shopping cart filled with plastic bags of all colors and sizes. Just under a dozen storytellers sat in the waiting room of the New York City Department of Probation’s Bed Stuy office. Instead of meeting with their POs, they were there to participate in the first session of a ten-week writing program Probation hired me to facilitate.

HOW TO APPLY MAKEUP (Guernica)

Step 1: Moisturize and Prime

Begin with well-moisturized skin. Make sure to do your research. Some moisturizers are mist-light, and others cream-thick. Some vanish deep in the dermis, while others leave a chalky residue. Oil-based moisturizers can be hydrating holy grails for dry skin or cystic kryptonite for oily pores. Find a moisturizer that’s right for you. Apply it evenly to your face. When dry, prime.

While moisturizer is the foundation for your look, primer is the framework that supports it. Some hydrate, nourishing dry, flaky skin. Others mattify, preventing oil-prone T-zones from ruining your look. Squeeze a dollop onto your fingertip. Tap from cheek to cheek, chin to forehead, leaving dime-sized dots. Smooth over the full surface of your skin.

At the mall for my biweekly visit, I bustle past the greeter with the scarlet lip. Her smoky eye is sculpted perfectly beneath her crisp pageboy bangs. “Welcome to Sephora,” she smiles. I watch her eyes and lips for any movement, my face angled her way. Her brows don’t bunch into a question mark; her lips don’t press into a sneer. This means I’ve done good. I can be confident that, today, I’ve applied my makeup right, despite my scars.

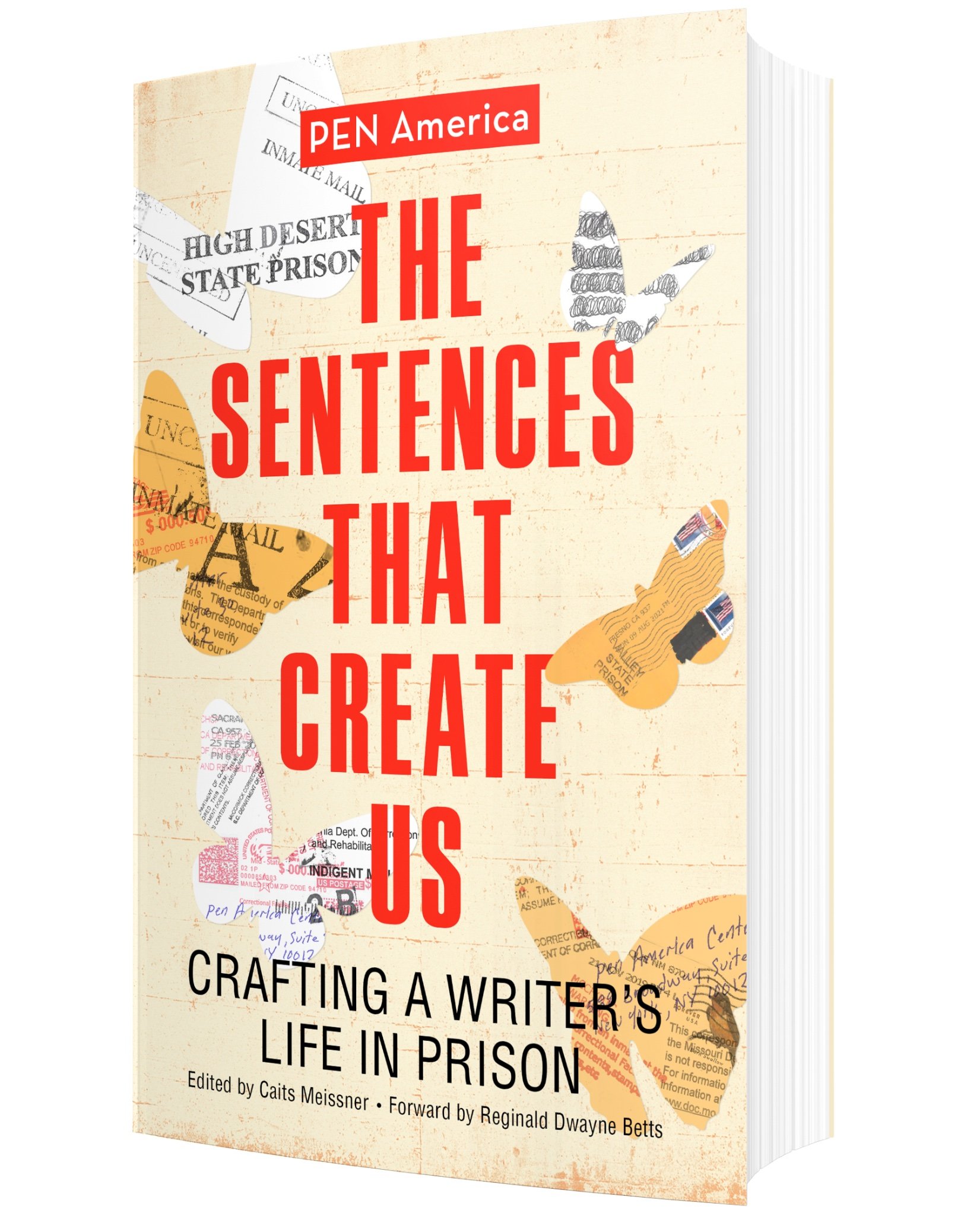

REMIX THE PLAN, RETURN TO THE PURPOSE (The Sentences That Create Us | Haymarket)

The waiting room was cramped. Self-care bulletins, hotline advertisements and glossy Department of Probation postings were taped on its green walls. In slanted cursive, a child-size Post It cautioned, “Please note, NYC Dept of Probation POs work 7 days per week. Any Departmental representative may/can visit your home, employment, program, school, or family members home. Thanks.”

Wide-legged and cross-armed, a young man slumped into a seat beneath the warning. Across the room, under a baseball cap’s brim, another’s eyes were closed, his head hung low as he napped. Next to him, a woman no older than twenty-five cupped her cheek with a palm, sculpted nails pressing into hair slicked into a high bun. Well past her fifties, a grey-headed woman sat behind a personal shopping cart filled with plastic bags of all colors and sizes. Just under a dozen storytellers sat in the waiting room of the New York City Department of Probation’s Bed Stuy office. Instead of meeting with their POs, they were there to participate in the first session of a ten-week writing program Probation hired me to facilitate. By the looks of it, but for the woman with the cart, no one gave a shit about who I was or what I had to say. The Department of Probation’s incentive worked. The storytellers were there because attending the class absolved them from reporting to their respective POs each week.

THIS SEAT IS FOR YOU (Sinister Wisdom)

Back in 1980s Brooklyn, I thought writing was something for wealthy white people with too much time on their hands. It was then, when I was in early girlhood, I learned that I was to make a living for myself, while nursing a baby and husband. Like Mama who was a legal secretary caring for me and crack-addicted Daddy. Mrs. Huxtable who lawyered while schooling five kids and cleaning up after Cliff’s mess. And, Raj and Dee’s Mama who was a maid and worked relentlessly to get Raj, Rerun and Dwayne out of all those jams. But, being a writer wasn’t a thing to aspire to. Not for us poverty-born Black girls. Being a writer, it seemed, was a thing only for Jessica Fletcher and other phantom white folk from whom I was worlds apart.

Each day when the dismissal bell sounded and I jumped into the single-file classroom line, Mrs. Powell marched my third-grade class toward the school’s exit. Outside of Brooklyn’s Public School 139, kids bounced about, played tag and tossed balls, eluding parents for end-of-school fun. I bypassed them all, following Mama’s before-school-orders to, “Head straight to the library and wait for your father to pick you up.”

The library was around the corner from the schoolyard. It was my favorite place to be. Once there, I hunted out the day’s treasure—a book by R.L. Stine, Ann M. Martin or Edward L. Stratemeyer. I’d plop onto a plastic yellow chair and perch my book stack on a corner table. Page after page pulled me deeper into imagination. But page after page also let me down. While I loved the adventures that Goosebumps, The Babysitters Club and The Hardy Boys presented, those books—and all the others I pulled from the library shelves—didn’t reflect the crack epidemic that flamed around me. They didn’t conjure my community, our faces, our slang, our blocks. In their pages, I didn’t see myself.

EXORCISING WHITENESS: KHALISA RAE’S GHOST IN A BLACK GIRL’S THROAT (The Rumpus)

I was new to the seventh grade when Ms. Rossi routinely refused to acknowledge me. Though my hand stabbed the air in response to questions she posed, Ms. Rossi never called my name. “What d’ya think, Hillary?” or “Rebecca, you give it a go!” Each time Ms. Rossi’s eyes roamed over my hovering wicker-brown arm and landed on a white girl’s freckled face, her lesson, reserved for the few Black girls in her “gifted” class, was reaffirmed—keep your hand down and mouth shut.

In Ghost in a Black Girl’s Throat, published by Red Hen Press last month, Khalisa Rae has written a haunting and holy gospel. At once a book of genesis and revelation, Rae’s full-length debut collection unveils white supremacy’s forging by fire of Black girls into circus, freak show, tightrope walker, stage performer, crazy. Rae does this through the lens of a Black woman who journeys from the Midwest to find a home in the American South, chronicling the inescapability of misogynoir’s violence. In “Ghosts in a Black Girl Throat,” the collection’s opening poem and origin story, Rae begins her proverbial sermon with the why of whiteness’s attack—

… And that’s what they will come

for first—the throat.They know that be your superpower,

your furnace of rebellion. So they silence

you before the coal burns…The leash will always be taut, gripping

around a word you never said…

KEEP YOUR BIBLE: I FOUND MY QUEERNESS IN BLACK RELIGION (Temple Indigo)

I floated alone.

The sun’s Jesus piece gold sliced through the ocean’s mild oscillations. Glancing around, chin crossing over chest to shade one shoulder before the next, I surveyed the unfamiliar expanse. My face soaked up the luminary’s warmth, like bee suckling nectar. Though neither landmass nor sign of human life, neither boat nor waterworn plank could be found in the sea’s vast, I was calm. My arms stroked, legs stretched forward and back, unshackled from burden. That I was by myself in an ocean didn’t startle me. Neither did the man who plowed up through its lid.

Droplets cascaded down his whiskey brown face, high cheekbones, his chiseled chest. A skirt of bark covered his body, waist to water. The man hovered, beautiful and fierce, and looked down upon me with an unsmiling, unflinching affection.

“You. You embody masculine and feminine better than them all. The Others,” he urged, “they think they have to conquer the seven seas to find the balance you hold. But you. You know you have to find the twelve.”

I said nothing, just listened, stared at his face.

A blink later, he disappeared. The ocean was gone. Instead of treading water, I laid in an old cast iron tub that, I recognized, was in my apartment’s bathroom.

A blurry haze projected from my bedroom’s television and filled my actual eyes, now that they were open.

Your Dog Walker Is a Felon: My Journey Through Probation’s Precarity (SLICE Magazine)

It wasn’t even seven in the morning on Thanksgiving Day, but Aspen growled as the man with salt-speckled hair and his purse-sized Pomeranian dashed by. Although they were at least five feet away from us, Aspen’s snout stretched, flashing sharp canines.

“Calm it down, Beautiful,” I coaxed, reaching over Cameo to pat Aspen’s fleshy underbelly. “We’re alright.”

Once man and dog were both beyond reach and out of sight, Aspen, Cameo, and I continued our walk. It was our second of the day. Not one of us seemed to mind.

We traversed the usual route, pouncing along Dekalb Avenue onto Tompkins and up to Herbert Von King Park. Amid almost barren branches and fields littered with stiff leaves, Aspen galloped like a thoroughbred and Cameo bounced tabby-spry into leafy mounds. At ease, I watched the girls play, tossed sticks for them to chase, smiled when their bodies banged against each other, and scooped their poop. Thirty minutes after arriving, frolicking in fall’s foliage, and chasing bemused squirrels, we hustled down Lafayette Avenue, cut a left onto Throop, passed the bitter-earth aroma that billowed out of Burly Coffee’s doors, and landed back in front of the new construction Aspen and Cameo knew as home.

Read More —>

Burn. (Inkwell Black)

Burn.

The nation is burning.

Long before George

and Breonna

before Atatiana,

Mike and Philando

before Yusef’s 16-year-old black body

was found bloodied

bullet-ridden

in Bensonhurst

before crack rocks cooked

in sooty pipes

over high flames

before Bushwick’s Broadway burned in 77

We have blazed.

Do you know the anatomy of a fire?

…

Read more —>

Granada (Kweli Journal)

Mama was dark liquor brown but only drank Bacardi Light. She wore natural three-inch long nails silk-wrapped and well-manicured. Whether in a business or bathing suit, matching heels were a favorite accessory, second only to her nails. Foam-roller curly hair bounced on her shoulders. Dainty gold earrings looped from her lobes. A stack of intricately etched gold bangles rounded her wrists. A gold link bracelet wrapped around her ankle. Depending on the weather and the occasion, a tailored blazer, butter soft leather trench or full-length beaver curtained her back. On weekday mornings, when she headed to the law firm where she worked as a legal secretary, a faux alligator skin purse dangled from her shoulder.

It didn’t matter if it was a weekday or weekend, professional event or house party, Mama stayed fly.

After work, Mama picked me up from Grandma Mabel’s Bushwick house. Even though we moved out of Grandma’s grand italianette earlier in 1984, Grandma Mabel still took care of me when Mama was at work. Finally in our new Fort Greene neighborhood, Mama pulled her purse’s thin strap back onto her shoulder and gripped my palm as we walked down Ashland Place. We swung hands while Mama sang to me, “I love you. I love you. Honey I, love you. I do. More than you ever know. It’s for sure…” Mama’s mezzo-soprano was butter smooth, while her alto smoked like brimstone. Sarah, Billie and Etta were among Mama’s favorites. Patti, Stephanie and Anita, too. When Mama pushed their songs from her mouth, as she often did, I’d look up at her with stretched cheeks.

Mama could sang.

A List of Violations (CURA: A Literary Magazine of Art & Action)

After I pled guilty to telecommunications fraud in a Cuyahoga County courtroom, and the judge sentenced me to eighteen months of probation, my lawyer cuffed my arm into his hand and ushered me onto an elevator. “Julie will take care of you. She’s the best probation officer there is,” he said, shifty-eyed and ready to be rid of me. I stared past puffy eyelids at the closing elevator doors, petrified of what was to come.

“You’re gonna be alright,” Probation Officer Julie Fritz assured, not even twenty minutes after my guilty plea. I sat hushed in her court building office chair. Bargain store-flimsy tissue pieces speckled the kohl black eyeliner and mascara that raccooned my eyes. “You had the best judge there is,” she went on, a wide smile and chestnut hair framing her face—Kathy Bates in Misery style. “We had another judge who did time for beating his wife. Nearly killed her. He came out and now he works for the mayor! No, he isn’t making the money he once did. But he’s got a decent living,” she offered all earnest.

My mouth stayed shut.

I thought about the judge’s wife.

“Here are the conditions of your probation,” Fritz said, thrusting a thin solitary sheet my way. “Just sign it and I’ll give you a copy.”

…

WE CAME. (Emerge)

We came from all five boroughs. Your Timbs smacked at concrete curb. A silver world at your back. Forty off to your side. The Bridge miles away. You headed past the matchbox frame forest and creased lawns sprouting

patchy like beards. On Sutphin, you waited for the Q6. Planes hummed high until you dipped low into the subway. You packed a pocket seat. Legs spread wide as your scowl. The E train shuttled you forward. Like a bullet through teeth

.

A 20-year-old woman was hospitalized

and suffered a broken spine after being

attacked by a man using anti-gay slurs,

according to the New York City Police Department.

The man fled the subway system at a Forest Hills, Queens stop.

NBC News

We came from all five boroughs. You walked a neck of weather-worn road. Between cast iron hedges and towering brick. Beyond ash black rubber squares waxing ground chandeliered by squeaky swing sets. You followed the mossy river that dandled your nose. And headed down the hill to catch a dollar van. On the ferry, you rode the lowest level. Sitting outdoors, you sucked smoke from the blunt pinched where your index met thumb. Your durag’s tail wind-slapped like a cape. The City before you beckoned. The Uptown 1, half a harbor away.

How Queen Latifah’s Debut Album Sparked Joy at a Time When Everything Burned (ZORA)

It was 1989 and I was eight years old when I arrived at the colossal red-brick building in Brooklyn where Mama, Daddy, and I lived. After hustling through a cracked cement courtyard and passing a thick metal door, I ran through the marbled lobby, bounded up the stairwell two steps at a time, and landed in front of apartment 2H. I pushed the key that swung from a snaked lanyard around my neck into the lock. I entered our apartment, rubbed Twilight’s tabby spine, and turned on the TV. After a few clicks at the remote, the cable box switched stations. Yo! MTV Raps was on.

A woman appeared on screen rocking black threads with golden cuffs and a tribal sash to match her shoulder’s adornments. She ambled through a dusty industrial park beneath a large, rusted wrought iron sculpture. Flanked by two other women uniformed in Kente blazers and black shorts, the woman walked straight-backed with measured steps. Juxtaposed against her formidable disposition and the dreary setting was a buoyant beat that bumped beneath smooth feminine vocals: “Ooooh, ladies first. Ladies first. Ooooh, ladies first. Ladies first.”

THE BUTTAH-FLY EFFECT: HOW SEX WORK TAUGHT ME SWAG (ColorBloq)

It was a busy Friday night at Uptown’s Harlem Heat. Although it dropped a year before, Lil Kim’s Hard Core bumped from the large speakers that stacked the stage. At least six girls were in rotation, working the ceiling-high poles. They rocked glitzy platformed stilettos, pleather g-strings and feathered garter belts. Asses clapped and men sprayed money like mace into the air. Those sitting further back from the action begged for attention from women who bared skin. A lacey black bodysuit boxed in my grenade small breasts, spear slim waist, barrel thick thighs. At seventeen, I chose this modest outfit because I was insecure about my body. And disliked the way men prowled my flesh when a four-foot high stage didn’t separate us. I pulsed through the packed floor beneath scarlet strobe lights. Calloused fingers grabbed at mine as I headed to my destination. “Two screwdrivers,” I urged.

Lil’ Kim spat: I, Momma, Miss Ivana. Usually rock the Prada, sometimes Gabbana. Stick you for your cream and your riches. The bartender, a petite boricua in satin pun pun shorts and a skimpy tank, plopped the drinks on the bar top. Although I performed on a few stages before tonight, my belly bustled with nerves. A novice stripper, I was afraid that my performance would be lackluster and that I wouldn’t make the money I desperately needed. As I downed the watery vodka and orange juice mix, a low-eyed cat slunk next to me. “Yo, how much you charge, ma?” he asked.

No One Survives The Smoke (Gay Magazine)

Coney Island, Brooklyn. 2017.

I pull onto Daddy’s block. The stocky frame houses stack next to one another like planks on the Boardwalk. It’s late fall so there is ample street parking, unlike the summer months when cars crush into each other like Colt 45 cans. A distant car horn buzzes angrily on the ave. Roxy barks from behind the ground level window that overlooks the street. Daddy stands in his front yard behind the tall guard gate, eyeing me as I line my car up against the stretch of curb in front of his house.

He pulls one last drag before flicking his stogie to the cement, heading in my direction.

Flatbush. 1987.

Mornings are the same in our busy one bathroom apartment. I lean onto the sink. My left palm anchors against its cool as I tiptoe, hoisting high enough to see my six-year-old reflection in the mirror. Gripping a small pink toothbrush, I studiously scrub the bubblegum-tasting paste side-to-side, across my top front teeth and the gap that’s smacked between them. Scccrppp scccrppp scccrppp…

Walk(wo)man (Rigorous Magazine)

A month after my arraignment, I hit the 92Y for the first time. Lena Waith in Conversation with Charlamagne the God, the Y advertised. When asked about life after earning an Emmy, Lena responds, “There's a difference between how you walk on this earth when you're living your dream versus how you walk when you’re thinking about [it].” Goosebumps feather my arms. I scooch deep into the mint green velvet chair.

When Charlamagne asks about the inspiration behind her penned Chi characters, she says, “Little black boys are not born with a pack of drugs in one hand and a gun in the other.” I snap my fingers, spread my legs and lamp my head on the seatback. The ceiling is at least a hundred feet high.

And, about her childhood in Chicago, she jests, “I grew up in a two-parent household – my mom and the television.” The crowd laughs. A shared nostalgia breaks free through applause. With my neck craned back, I see that the richly polished auditorium walls wear dead men like halos. Beethoven. Lincoln. Washington. David. Moses are written at the ceiling’s edge, all-capped in faux gold. I remember my own come-up and grunt, “ummm humph!”

Because of crack, TV became my daddy.

But, music was always my God.

Men Rape Us and You Let Them (For Harriet)

Men rape us.

They rape us in corner offices, and in cubicled workspaces. They rape us on college campuses and in correctional facilities. They rape us in million-dollar shiny glass residences – gaudy golden. And in pissy project stairwells under dim lights while kneeling on sticky steps.

Men rape us.

Stalking and hardly slick in plain sight, men prey on those of us who are innocent, and us indomitable ones, too. Those of us who are trying to get put on, and us already kissing the glass ceiling. They R. Kelly piss and fuck on those of us too young to understand rape’s breadth, and those of us who are Anita Hill, old enough to know that he won’t be held accountable.

Men rape us. And, women join in shaming us silent.

They shame us for not going to the police. They shame us for waiting too long to file a report. They shame us for being girls with asses that roll like mountains when we walk. For being women with breasts that bounce even when barricaded by bras. For having no ass or tits at all. For being pretty. And ugly too. These muthafuckas shame us for breathing.

Nemo Tenetur Seipsum Accusare

Boom. Boom.

BOOM.

Sharon sprung up, hinged at the hip, as she sat in her bed, her torso slightly tilted forward as if leaning closer to the bedroom’s door would help her listen past the sound of her heart thump, thump, thumping. She anchored, stiff-backed and paralyzed. Only her chest moved, as she inhaled, exhaled, her ribs constricting each breath and heartbeat. And her nylon baby doll nightie, its right strap slid from her shoulder down her arm, resting beneath her elbow. Pulling down the thin fabric across her torso, exposing her right breast.

Ray Ray came home last night, didn’t he?

Book Review The NYPD Tapes: A Shocking Story Of Cops, Cover-Ups And Courage

IN MAY 2010, THE VILLAGE VOICE published a series, penned by then staffer Graham Rayman, about widespread crime statistic manipulation, routine police officer intimidation and broad corruption within the New York City Police Department. In August 2013, a mere week before Federal Judge Shira Scheindlin’s Floyd v. City of New York decision, which declared the NYPD’s stop and frisk practice unconstitutional and racially biased, Rayman published the

book-length version of his NYPD expose.

In The NYPD Tapes: A Shocking Story of Cops, Cover-ups and Courage (Palgrave Macmillan,

2013), Rayman provides the reader with insider information never before revealed to the civilian masses who live and work outside of One Police Plaza, the most famous blue wall.

In the opening pages, Rayman immediately pulls the reader in while describing the tale of

two New Yorks: the New York that boils at the injustice of a white tourist’s skull being crushed versus the New York that is apathetic to the death of a bullet-ridden black teenager; the New York that is associated with the high-rise-pocked Manhattan skyline versus the tenement-laden outer boroughs of Brooklyn and the Bronx; the New York that boasts the greatest police force in the world versus the New York whose beat cops are intimidated by commanding

officers into fudging the numbers.